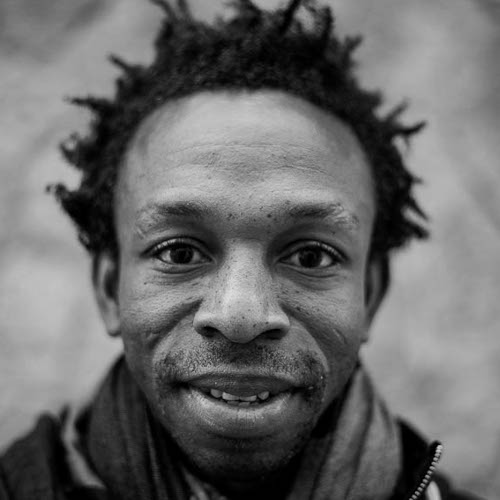

Ousman Umar

Birth place

It is said that our childhood leaves a permanent mark on us for all our life, except in my case, it was a stage where there wasn’t space for this to develop. I was born in Africa, in a village called Fiaso, Ghana, on a Tuesday in 1988. As a child, I had very little to enjoy, so I had to invent my own toys and games. When I was thirsty I had to go to the river to fetch water. My house had nothing. If I wanted to eat fish, I had to fish for it in the river. I was the son of the shaman of our village and I sometimes had to go into the jungle to look for specific plants to cure the illnesses of the people from the surrounding villages.

When I was thirsty

I had to go to the river

to fetch water.

It all began one day while I was playing soccer with my friends after taking care of the animals. Suddenly I saw an airplane flying overhead and I thought: “how is it possible that an airplane is up there flying? If I take anything and throw it in the air it falls to the ground, so how is it possible that this doesn’t happen with the airplane?” I compared this with the toys that I had made and those that I had to drag along the ground if I wanted them to move. I was once told that people with white skin were the ones that could fly planes.

From this day on, I began to think that the world existed way beyond my place of birth. So, I started to move outside of the boundaries of my village. I envisioned the white man as a god because Europe was considered a “paradise” and I was convinced that the “white man” was a synonym of intelligence, a doctor, and engineers… to sum it up, as superior beings. This idea did not strengthen my thoughts, but it was the first time that the idea entered my mind to leave my country in order to get to know the white man.

From this day on, I began to think that the world existed way beyond my place of birth. So, I started to move outside of the boundaries of my village. I envisioned the white man as a god because Europe was considered a “paradise” and I was convinced that the “white man” was a synonym of intelligence, a doctor, and engineers… to sum it up, as superior beings. This idea did not strengthen my thoughts, but it was the first time that the idea entered my mind to leave my country in order to get to know the white man.

A couple of years later I was able to get a job in a nearby village. After this, I moved to the second capital of the country and finally arrived at the port in the capital city, Accra. It was there I was so fortunate to watch television for the first time in my life. It was on that same day that Barça happened to be playing. As I had been working at the port, I often saw ferries, cars and machines in general. From this moment on, my interest to get to know the white man grew more and more. I kept wondering how they were able to create and develop such amazing things.

I was only 12 years old at that time, illiterate too, dreaming about a continent that I couldn’t travel to. I worked as a welder. My hands and body were small and stable which allowed me to enter into the complex machinery where welding wasn’t at all simple.

my salary only

allowed me to buy

one bowl of rice

per day…

One day I heard someone talking about Libya. I was told that if I moved there, I would earn more money which I found impossible due to the fact that until that moment in Accra my salary only allowed me to buy one bowl of rice per day. Needless to say, I accepted the offer.

“JOURNEY” ACROSS THE SAHARA DESERT

The trip I undertook still seems like a movie to me, so surreal that it couldn’t have happened.

I often say to myself “How did I survive”? An example of this happened in the Sahara desert with 65 of us distributed in 3 Land Rovers (18 people in each), crossing among the dunes. Suddenly we were told to get out of the cars because the drivers “had to refill the gas tanks” and they wouldn’t take long to return. They never returned. We were left stranded in the middle of the desert. In spite of this, one boy assured us that he knew the right way to go and we decided to follow him. He took advantage of this by making us pay, if not, he wasn’t going to guide us.

Days passed and with the group we were faced with more and more setbacks. We had neither food nor water. “One of the things that I learned from this experience is that the human body is truly wise and adaptable to every situation. After 21 days only 6 out of 56 that started out on this journey arrived at the other end of the Sahara. We survived.

After 21 days

only 6 out of 56

that started out on

this journey arrived

at the other end

of the Sahara.

“I gave up many times throughout the course of this journey. I lost hope. Those were such difficult moments.” With time, I think the worst moment came when we spent 18 days walking across the desert. We no longer had food nor water. We had nothing. There were members of the group dying in front of my eyes. I had no hope to keep me alive. The situation 3 days prior was that our “leader” had left the group stranded taking our possessions and money with him. Luckily I saw a dead body next to a large stone. Overtaken with fear, I walked toward him and looked in his pockets and found a canteen full of water. “That saved my life. I asked myself why it had been me who found it, but I thank God for choosing this arduous road.”

When we arrived in Libya the situation was worse than we had expected. At that moment the country was under the rule of Gadaffi. Black immigrants were mistreated. “A dog was worth more than a black immigrant”.

JOURNEY IN A DINGHY

I was in Libya for 4 years and able to save enough money to flee the country. The mafia convinced me to pay $1,600.00 to cross the Mediterranean and eventually into Spain.

“We’ll take you, it will only take 45 minutes” they assured me. I wasn’t able to prove if this information was valid. A new problem arose.

The mafia convinced me

to pay $1,600.00 to

cross the Mediterranean

and eventually

into Spain.

The problems with mafias originate from a long time ago. It isn’t only mafias but the other people involved (the police who worked during the day worked for the mafia at night). This was the result of the political agreement between France and Argel during the Sarkozy administration; for every immigrant arrested, the police received a payoff.

“We were severely mistreated”: during the day the police did their job. At night they became perverse. Even so, the mafia provided us with material and equipment to build our own boats. Once we had finished I felt brave enough to get on one of them. I didn’t how to swim. It took us two attempts to get into the sea. At the first try the boat collapsed against the waves. Ten people lost their lives. One of them was Muusa, my best friend.

After this failed attempt we returned to the desert. I remember losing my shoes and had to walk barefoot for one month. Thirty days later, the mafia gave us new materials to make 2 new boats. There were 60 of us per boat, and this time the other boat sank. Ours, on the other hand, took us to Fuerteventura (the Promised Land). A friend of mind told me: “get up, my friend! Let’s walk! I was exhausted!

The boat crashed against the rocks and it turned over right in front of the shore. I thought I was going to die. Fortunately, I made it to shore and felt so relieved. The waves dragged me to the beach. I wasn’t even able to stretch my legs out after having been on the boat for 24 hours. I couldn’t walk because my feet were full of scars. My companions walked to a lit road and I concentrated on trying to follow them. It was a dark rainy night.

The police appeared with the Red Cross and the media. They were tending to my companions and gave them blankets. Later they shouted “Look, there’s somebody else! The Red Cross came to me and covered me with blankets. In my case, I had to be taken to an ambulance because I was shaking.

After this we had to sign several documents and then we were taken to the Red Cross office. Later, they took us to the hospital and the doctors gave me an “age test” on my wrist to find out how old I was. I only knew that I was born on a Tuesday: this is the only thing that matters in Ghana when a baby is born.

…the doctors gave

me an “age test”

on my wrist to find

out how old I was.

I only knew that I

was born on a Tuesday.

I ended up staying in prison for approximately one month. Every two or three days I was taken to an interrogation room which was small and dark. I was questioned and made to confess something, but I had nothing to confess.

I was so lucky to hear that after this period, the state of Spain offered me the possibility to live here. Following this, I flew to Malaga in a small airplane where I was asked what city I would like to live in. I didn’t know Spain nor the most important cities. I then remembered while in Accra I had seen a soccer match on television where Barça was playing. So, I said “Barça”. They understood what I wanted to say. Barcelona was my final destination.

Arrival in Barcelona

24TH FEBRUARY 2005

They gave me a tuna sandwich, a bottle of water, a banana and a one-way ticket to Barcelona. I was in Barcelona for the first time in the winter of 2005. When I got there I felt so happy for not having asked for the address of the Red Cross office in the city. I walked around the city looking carefully at everything I saw. Cars, houses…everything was so new and amazing. I remembered that I greeted everyone around me which is customary in Africa. People gave me strange looks. Eventually, it got dark and I didn’t have time to go to the office so I ended up having to sleep somewhere on the street.

I woke up the next day near “La Meridiana” sitting on a bench. I saw a woman passing by slowly. I got up and politely approached her. I showed her all the documents I had on me and explained who I was and asked where I could find the Red Cross office. She hardly spoke English and didn’t understand me. Anyway, she seemed to show empathy toward my situation. She took my hand and phoned her husband who spoke English. I was able to speak to him without difficulty. After that, the woman invited me to have lunch and gave me her phone number. She asked me to phone her if I had to sleep in the street again.

Following the directions of that kind woman, Montserrat Roura, I managed to go to Plaza España. When I got there I felt stressed. I didn’t know how to read the map of the metro. Suddenly I heard a female voice behind me. I was very frightened because in Libya the men cannot talk to women. This woman was called Eva and she helped me a lot. She showed me where the Red Cross was and recommended that I go there on my own. (Except in the case that they didn’t accept me). She gave me 40 Euros, a backpack and went on her way.

I was sent to a sports complex where I spent 3 nights. But the fourth night I was sent out and had no choice but to sleep on the street again. I slept on benches for 1 month. It was exhausting. At that point, I made the decision to phone Montserrat (she had given me her phone number sometime before) and I explained my situation. Following a long conversation, she and her husband were willing to talk to the people at the Red Cross. Montserrat and her husband were so generous with me and became my guardians. (I was not yet a legal adult).

My new life had begun. On the first day and after dinner, my new mom came to say good night and kissed me on my forehead. She turned out the light and left. My first night was really tough. I couldn’t sleep, I cried. I didn’t understand why I had to live such a horrible journey to eventually feel sure in my new home. It was the first time that someone had given me a kiss. I felt that someone loved me after so much time had gone by. In Africa, the concept of physical contact is so different, the people shake or touch the hands of others to show their gratitude.

Finally, I came to a conclusion: the question shouldn’t have been about “why?”, instead, “for what purpose?” In what way was my experience going to be useful? The answer was clear: now I have to transmit and inform others of my experience to raise awareness about where I come from. There has to be a way to improve living conditions in Ghana and the most important, I have to do everything in my power to avoid that other people suffer from the same experience that I had undergone. The possibilities of losing lives are too high.”

…the question shouldn’t

have been about “why?”,

instead, “for what

purpose?”

I began to study Catalan and Spanish and was able to obtain my high school diploma. I then studied Chemistry in the University of Barcelona and after 2 years I had to leave my studies because I had to work in my job as a bicycle mechanic in order to pay for my college expenses and to be able to do an internship simultaneously. I decided to change to another degree program in Public Relations and Marketing. I finished my degree and a year later completed a Master in Management, Administration and organization of NGO’s at ESADE.

NASCO Feeding Minds

In 2012 I founded the NGO NASCO Feeding Minds with the aim of providing access to information and education, reducing the digital divide. My focus is to avoid the youth in Ghana embark on life-threatening journeys like the one I had undergone. Had I been aware of the distances, risks and location of Europe, I would never have left Ghana as I did. Education is the tool to change every society.

My focus is to avoid

the youth in Ghana

embark on life-threatening

journeys like the one

I had undergone.

With the creation of NASCO in 2012 I had to buy 45 computers with my own money as a mechanic following the unsuccessful “crowdfunding” approach I initially opted for. I thought that this was a very important and necessary tool. It is a way of building bridges and opening a door to the world for the underprivileged students in Africa, beginning with Ghana. These 45 computers were sent to a secondary school in San Agustin which is in the northern region of Ghana. We began with 850 students and 2 ICT professors and today in 2020 more than 20,000 students in 11 classrooms have taken part in our initiative. A total of 30 schools are benefiting from this program.

Later I discovered that the entity called Social and Corporative Responsibility of Companies exists and that every four or five years they replace their computer equipment because they are considered obsolete. Thanks to this initiative many companies have donated their equipment so that we are able to make good use of them to open new classrooms in Ghana.

In addition, I began to share this experience here, with schools for children who have everything they need but do not take profit of or do not value the right to have access to education.